Howard: So, I recently pointed Todd to a nifty-looking Kickstarter for a deep space exploration expansion for Traveller, and it got the two of us talking about what is arguably the best-known science fiction role-playing game, and one of the first.

Todd: “Arguably” is right. We were arguing, because of how wrong you are.

Howard: Future generations will decide that, my friend.

Todd: Before passing this debate off to future generations, let’s spend a moment telling this generation why this is so important. Namely, what Traveller’s all about, and why it’s so crucially important to SF gaming, and science fiction in general.

Howard: Fair enough. Have at it.

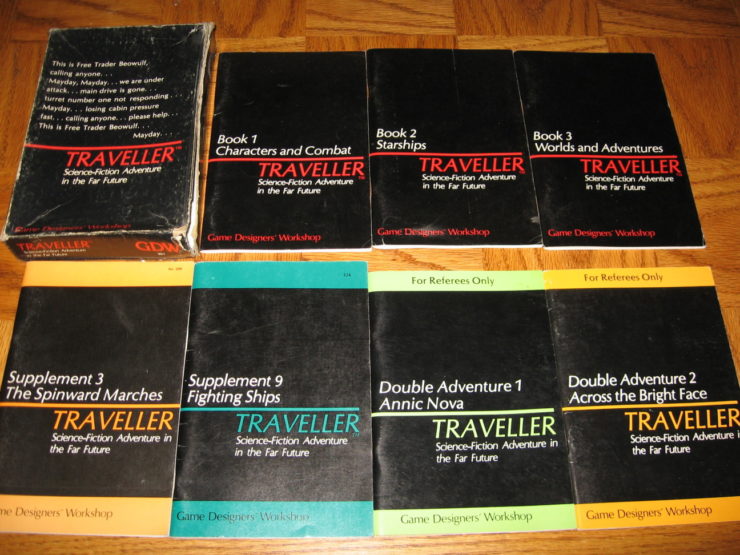

Todd: Traveller was the first major science fiction RPG, and it’s certainly the most influential. It was released in 1977, just three years after Dungeons & Dragons, by the tiny Illinois game company Game Designers Workshop (GDW). The success of that first boxed set, which we call Classic Traveller these days, helped propel GDW to the forefront of adventure gaming in the ‘80s and ‘90s. The first edition was designed by Marc Miller, with help from his fellow GDW co-founders Frank Chadwick and Loren Wiseman, and Dr. John Harshman.

Howard: Just as you can see the influences of older fantasy fiction on Dungeons & Dragons, you can clearly see how older science fiction had an influence upon Traveller, which, like D&D, was shaped by certain speculative fiction traditions and then became a cultural force in its own right.

Todd: Absolutely right. It’s fair to say that Classic Traveller was basically a ‘50s/’60s science fiction simulator. It was deeply inspired and influenced by the mid-century SF of E.C. Tubb, H. Beam Piper, Keith Laumer, Harry Harrison, Isaac Asimov, Jerry Pournelle, Larry Niven, and most especially Poul Anderson.

Howard: Classic Traveller was very light on setting—

Todd: To put it mildly!

Howard: —but it sketched the scene in broad strokes. Players adventured in a human-dominated galaxy riven by conflict, thousands of years in the future. The star-spanning civilization of that future looked an awful lot like the galactic civilizations imagined by Asimov, Anderson, Jack Vance, Gene Roddenberry and others.

Todd: It sure did. Gary Gygax famously cataloged his influences in Appendix N of the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Unfortunately that first Traveller boxed set didn’t have an Appendix N, but its inspirations were obvious for anyone who cared to look. Game blogger James Maliszewski did a stellar job laying out Marc Miller and company’s influences from the forensic evidence in the first edition, in the cleverly-named “Appendix T,” published at Black Gate back in 2013.

Howard: But before you could START adventuring, you had to play a mini-game to create your character.

Todd: Yes! This was one of the uniquely idiosyncratic elements of Classic Traveller, and maybe the thing it’s best remembered for.

Howard: Character generation basically simulated your military career, where you picked up all kinds of interesting things like engineering, gambling, bribery, computers, administration, piloting, and gunnery. If you were dissatisfied with your skill set you could do another tour of duty before mustering out. Of course, another tour made your character older.

Todd: And possibly dead.

Howard: Yeah, there was a chance every tour of duty would kill you, which was a bitter twist when you were finally rounding out that hot shot space pilot. Traveller never sold quite as well as D&D—

Todd: Probably because that game didn’t kill you during character creation.

Buy the Book

Repo Virtual

Howard: Well, every game has its flaws. Besides, unlike its old school competitors like Space Opera or Universe or Star Frontiers, all of which faded away after a few years, Traveller never truly died. Sure, various Star Wars or Star Trek rules briefly outsold it from time to time, but those license holders eventually had to relinquish it, and then someone else would pick Trek or Star Wars up and invent a whole new game system for either setting. Traveller just keeps on flying.

Todd: Despite the generic setting.

Howard: Okay, now we’ve reached the core of our argument. Go ahead and state your case for the jury, please.

Todd: It’s pretty simple. For too long, Traveller didn’t have a setting. It was a generic science fiction simulator, and it lacked any real personality. That was a major flaw, and I think that’s why it never achieved the breakout success it deserved.

Howard: That’s too harsh. Classic Traveller was a simple way for players who enjoyed classic science fiction to replicate the same thrills in a role-playing game. It was sandbox rules set we could adapt to any setting we wanted. A default setting wasn’t necessary.

Todd: That might have been fine for 1977, but as role-playing games rapidly grew more sophisticated in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, a generic setting no longer cut it.

To its credit, GDW eventually realized this, and it gradually co-opted the more colorful setting it created for its other popular science fiction game in 1977, Imperium, a two-player board game that simulated the wars between the fast-rising Terran Confederation and a vast interstellar Empire in slow decline.

I played a ton of Imperium back in the day, and I’m glad that backstory found a good home. It was retconned into Traveller, providing the game with a conflict-filled galaxy split into a handful of political spheres, with plenty of lawless areas and opportunity for adventuring. But in some respects, it was too little too late, and it hurt the game.

Howard: Not nearly as much as you think. By the early ‘80s, just as role-playing games were starting to break into the mainstream and when I first started playing Traveller, GDW had developed the Third Imperium setting.

And what a cool setting it was! A loose federation of human and non-human races, the Third Imperium is rising out of the ashes of the interstellar disasters that precipitated the fall of the Second Imperium and the Long Night, and you know what that means—lawless sectors of space, forgotten technology, abandoned outposts, alien incursions, strange rumors, and all the delightful apparatus of classic science fiction adventure.

Looking back, it’s clear the Third Imperium still had its roots in GDW’s science fiction boardgames from the 1970s, which in turn were inspired by things like Asimov’s Foundation and Poul Anderson’s Psychotechnic League. But that just made it familiar, and maybe that’s what we were looking for in those days. It certainly fired my imagination, anyway.

Todd: I have to admit, that sounds a lot better than I remember.

Howard: Did you ever try any of the later editions of Traveller?

Todd: Not really. I mean, there’s a lot of them—Wikipedia lists no less than a dozen editions from various publishers since 1977, including MegaTraveller (1987), Traveller: The New Era (1993), GURPS Traveller (1998), and even a Traveller Customizable Card Game from Marc Miller (2017). The latest role-playing game, Mongoose Traveller 2nd Edition, came out in 2016.

I haven’t kept up with them all. Are they very different?

Howard: Aside from the card game? Not that much. I mean, there has been some tinkering and some attempts to get people who liked other rule sets to try out the Third Imperium setting. The main line basic rules system, however, remains pretty similar to what it was in the 1970s. There have been changes—there are far more universe-specific details available to bring the default setting to life, and you can no longer be killed during character creation!—but the system is still based primarily on the rolling of 2d6 against a target number modified by skills and attributes.

Todd: I don’t know. Is it really Traveller if your hotshot space pilot can’t die during character creation? It seems unnatural somehow.

Howard: It’s less quirky, I’ll give you that. The various editions over the years had interesting elements, but they never caught on the way the original did. There were brief experiments with a D20 setting, and a Hero setting, and Steve Jackson licensed Traveller’s Third Imperium setting for GURPS in the late ‘90s. But the recent Mongoose Publishing release, the second version of its own take on the license, is a full-color deluxe edition, and well worth a look. While you can still use the Traveller game system to create any kind of setting you want, the Third Imperium is the default, and it’s astonishingly rich.

I think Dungeons & Dragons is the best parallel here, because it’s the closest thing we have to a fantasy game system that’s as popular as Traveller.

Todd: But D&D doesn’t have one setting that continues to prosper. It’s had several, like the Forgotten Realms, Ravenloft, and Dark Sun, and they all have their followers.

Howard: But none can compare to the depth and complexity of the Third Imperium. Generations of writers have continued to create worlds and aliens and adventures, populating entire sectors with interesting places to visit, wonders to encounter, and terrors to avoid, not to mention curious trade goods and nifty-looking space ships. Just reading the setting material takes you down a wonderful rabbit hole.

Todd: I made the mistake of visiting the official Traveller Wiki the other night and it was midnight before I came back out. It’s incredibly detailed, as you can see here.

Howard: Like that aforementioned fantasy game, Traveller has impacted modern science fiction. A certain Whedon fellow has admitted that his show was inspired by a popular science fiction role-playing game that he played in college…

Todd: You’re the only person I’ve ever met who uses “aforementioned” in casual conversation. That’s why I love you, man.

Howard: Thank you. Here’s an interesting post breaking down the case for that game being Traveller, and I think it’s fairly convincing. If you don’t feel like clicking through, the writer points out a correlation between what was in print when Whedon was in college, the fact that Regina and Bellerophon and other Firefly planet names are well-known destinations in Traveller’s Spinward Marches, or even small things like the way Wash shouts “Hang on, Travellers!” or that the Reaver’s Deep expansion for Traveller came out while Whedon was in college…

Todd: Even if you don’t notice those connections, I think most players will find the feel of the game is very Firefly-esque. As you said, while it’s possible to play Traveller with any kind of science fiction concept— Star Trek style exploration, Honor Harrington-esque space battles, space mercenaries or pirates, or even Star Wars-style space fantasy—from accounts that I’ve read online it seems like most players ran campaigns that felt A LOT like Firefly, decades before Firefly existed.

Howard: I know the campaigns I joined were like that—we were playing characters with a small trade ship wandering from planet to planet having adventures, while trying to make ends meet.

Todd: While I loved reading about later editions of Traveller, I never got to play them much. So I’m going to phone a friend.

Howard: Can we do that?

Todd: Actually I’m just handing a phone to a friend. E.E. Knight, author of the Vampire Earth and Age of Fire series. Plus his brand new book Novice Dragoneer just came out last month.

Eric: Hey Howard!

Howard: Hey Eric—what are you doing at Todd’s?

Eric: He invited me over to help him build his new Lego Star Destroyer.

Todd: Pew! Pew!

Eric: I’m a big Traveller fan from way back. What I wanted to expand on here was the reason for Traveller‘s amazing longevity. It was like these Legos: you could build anything with it.

I don’t think the early lack of a setting hurt the game in the least. We all talk about Dungeons & Dragons’ famous Appendix N as a way to get additional ideas for your D&D campaign. Traveller was a game system built so you could use your personal science fiction Appendix N and make a campaign out of it.

Back when my group played it, our universe was a melange of ideas from authors we liked. There was a lot of H. Beam Piper’s Federation/Space Viking stuff, some Laumer Retief and Bolo gear, and of course Heinlein-style armored battlesuits. Alan Dean Foster’s Thranx and AAnn were running around, or something very like them. You could snap on just about anything. I remember we tried Universe and it was just too science-y and not fiction enough, and Star Frontiers, while it was an amazing world, wasn’t “ours” in the way the little favorite SF-gumbo we’d created felt.

Howard: That’s a great point. The more period science fiction I read, the more influences I discover in Traveller itself. For instance, having finally read the first two Dumarest novels by E.C. Tubb, I discovered the low berths, high passage, and middle passage, which figure prominently in the Traveller game. And some of the characters in the Dumarest books are even referred to as travellers!

Eric: The fingerprints of numerous science fiction classics are all over the game.

Howard: I love that, but I think the thing I love most, apart from the rich setting, is that the system is nearly “invisible” and not so much about rolls and classes. After you create characters you can pretty much just get to gaming and not worry so much about rules consultations.

Eric: Maybe it was just my GM’s style, but we found that to be true as well. Sometimes we’d just argue that our character had the skills and tools to do a job and we wouldn’t even roll. There’d be whole encounters with NPCs where no dice were ever picked up. Combat was rare-ish—and we liked combat, we were a bunch of guys who mostly played Avalon Hill or SPI wargames. But murdering your way through an SF story just felt wrong.

As I was relating to Todd earlier, I had this galactic archivist-by-way-of-Retief character with Admin-4 (a skill that helps you interpret and, when necessary, cut through red tape). Perhaps because we all had a Laumer-like sensibility that bureaucracy sends its tendrils into every corner of the universe, my GM found it amusing to take out a Final Boss with that skill: “With that third success, Dek discovers that the Compensated Quit Claim to asteroid DZ0-2188A, although apparently properly filed by Ratstink Galactic Minerals after Uncle Pete’s Last Chance Mining and Exploration Partnership was chased off, did not originate with the Mining Commission, therefore it’s undoubtedly a clever forgery inserted into the Archives by RGM agents after the discovery of those Valubinium deposits.”

Todd: I love that story! It’s a classic Traveller tale if I ever heard one. There aren’t many games that value admin skills—and give you the tools to turn them into great stories.

Howard: Battles were a lot more realistic, too. More than in, say, that fantasy game. I remember that we tried to avoid them unless we were wearing battle suits, because characters tended to die when hit with laser guns, or slug-throwing side arms.

Eric: We almost always had one major battle every session. We had the Snapshot supplement, which was a Traveller-based wargame of close-quarters battle on small starships, and tons of maps. So many maps. I even owned the Azhanti High Lightning supplement as well, which came with 14 deck maps for a huge military spaceship. If a Snapshot game was a shootout in a sub-level cargo hold, Azhanti High Lightning was like Nakatomi Plaza from Die Hard mapped out as a multi-level spaceship. But you’re right, if you wanted to survive, you’d better be wearing armor!

Howard: It’s still one of my favorite settings. When I think of D&D I always think of home-brewed campaigns and certain moments when just the right number came up on the dice. When I think of Traveller, I remember the Third Imperium and the stories, somehow more divorced from the dice rolling.

Eric: Traveller fills my emotional gravy boat because it’s the one game I mostly experienced as a player rather than through running it. The universe was ours, rather than Gary Gygax’s or George Lucas’s or Gene Rodenberry’s or who-have-you. I couldn’t wait for the next session to get back into it.

Todd: Gentlemen, I don’t say this very often, but you’ve convinced me. As much as I cherished that copy of Classic Traveller I bought back in the ‘70s, I think I was playing it wrong. Rather than lamenting the lack of a setting, I should’ve brought one of my own. Even it was cobbled together from my favorite SF novels and a teenage imagination. Maybe especially a setting like that.

Howard: It’s never too late, you know.

Eric: Exactly. I’ve still got my dice, and an extra chair for you Friday night.

Todd: Seriously? With my luck, my character will die during character generation.

Howard: Well, character death during creation is only possible now when you’re using optional alternate rules. But use them if you want: all great science fiction has an element of tragedy.

Eric: Or humor. Depends on how you look at it.

Todd: I’ll be there Friday. But I’m bringing my own dice.

Howard lives in a tower beside the Sea of Monsters with a wicked and beautiful sorceress. When not spending time with her or their talented children, he can be found hunched over his laptop, mumbling about flashing swords and doom-haunted towers. In 2019 St. Martin’s published the first two novels of his newest fantasy series, For the Killing of Kings and Upon the Flight of the Queen. Paizo has published four of his Pathfinder novels and St. Martin’s/Thomas Dunne two of his critically acclaimed historical fantasy novels starring the Arabian sleuth and swordsman team of Dabir and Asim. He edits Tales From the Magician’s Skull and for the Perilous Worlds publishing imprint.

Todd McAulty’s first novel The Robots of Gotham was published by John Joseph Adams Books in June of last year. He lives in Chicago.

E.E. Knight is the author of the Vampire Earth, Age of Fire, and Dragoneer Academy books. He and his family live in Oak Park, IL.